How to help your employees build resilience and improve their mental health: One size does not fit all

Mental health is finally a workplace topic of conversation, and it’s a welcome change.

No one deserves to be put through psychological abuse such as belittling, bullying, and gaslighting, and leaders have an obligation to handle those who use such tactics.

Life outside work also creates emotional taxes that people may carry into the workplace. The result can include adverse reactions to triggers that damage relationships. Wouldn’t everyone be better off if someone feeling extreme duress took a mental health day instead?

At the same time, employees in chronic mental health crises exhaust their co-workers, and leaders with fragile mental health may shut down or become abusive.

There’s an excellent chance that you are not a trained therapist, and you might be wondering what you can do when one of your employees struggles on the job to cope with setbacks or uncertainty.

The key is to provide the proper scaffolding so they can move forward.

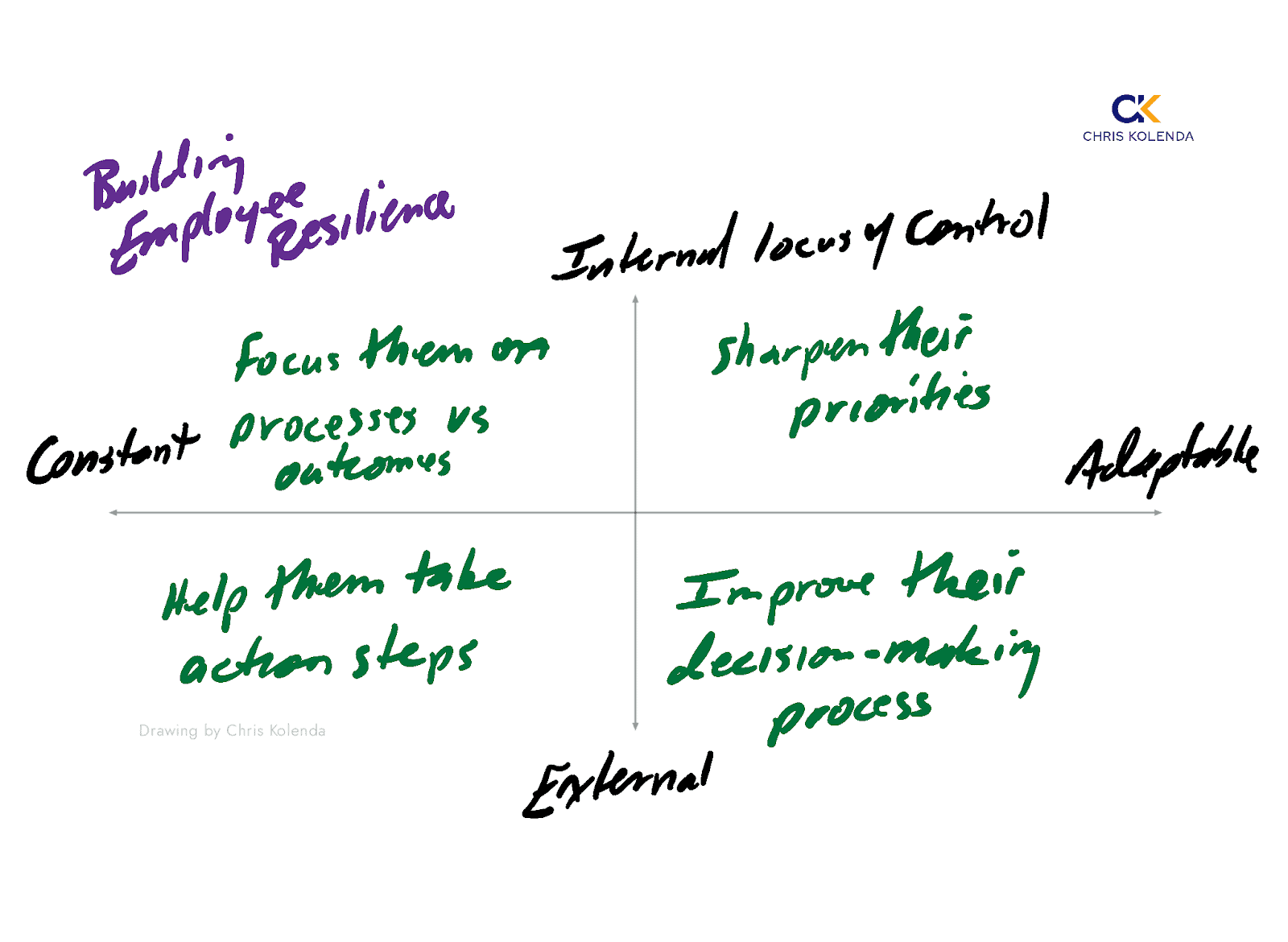

The chart below can help you provide actionable support for people in duress. The vertical axis represents their locus of control. Some people have an internal locus of control: they believe their actions are primarily responsible for the outcomes they experience. Those with an external locus of control believe that factors outside their control are responsible principally for outcomes.

The horizontal axis depicts flexibility: constant versus adaptable. Constant people tend to have deep convictions that guide them through the world, whereas adaptable people roll with the punches regarding matters beyond their control. A constant person may attribute the weather to divine intervention, while the adaptable person says there’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad clothing.

Constant people with an internal locus of control take responsibility and maintain their convictions through difficulties. On the downside, they can drift into Master of the Universe mode and have unrealistic expectations about their ability to control outcomes. They can beat themselves up and demoralize their teams when things don’t work out. Help them see that they cannot control outcomes, but they can control their inputs and processes. COVID, global supply disruptions, inflation, AI, and other externalities drastically affected outcomes. Those with sound processes rode the waves successfully.

Constant people with an external locus of control often go with the flow, believing fate controls their destiny. This can calm them in the face of uncertainty. However, they can shatter when something goes awry because they think luck, karma, and divine guidance are against them. You can support them by identifying small action steps they can take to move forward and gain momentum.

Adaptable people with an external locus of control are great at contingency planning. They can see the risks and opportunities from outside forces and create Plans B, C, and D to mitigate the downsides and seize opportunities. In the face of uncertainty and ambiguity, they can dither in paralysis by analysis. You can help them move forward using a simple, effective decision-making process (and here, too).

Adaptable people with an internal locus of control tend to show resilience in the face of challenges because they believe they can problem-solve and innovate to make the best of any situation. However, they can heighten others’ anxiety by ruminating out loud or spitting out new ideas at a machine gun rate of fire. Get them to explain their priorities and describe their game plan, and encourage them to stick to the new idea long enough to see it through.

This process also works for managing up, so you can help your boss get unstuck and back into action.

What topics do you most want me to write about? Send me an email or comment and let me know.