What Surgery Taught Me About Rule-Breaking

How often does rule-breaking occur in your business? Probably more than you’d care to admit.

Americans are avid rule-breakers. I think it’s in our DNA or the water or both. Many people came to America because they didn’t like their home country’s rules. Americans defy scolding self-appointed elites. Don’t tread on me.

We brought the Boston Tea Party, the Declaration of Independence, and a revolution that stirred other rule-breakers into action. During the Cold War, Soviet military officers feared the American military’s unpredictability: “The American military is so hard to understand because they have a doctrine, but they don’t follow it.”

Skepticism about OPR—Other People’s Rules—is pervasive and probably happens more often than you’d like in your business.

I had surgery recently to repair several nose injuries I suffered in the Army that impeded my breathing. (Cue the wisecracks about the lack of oxygen in my brain, which explains a lot.)

A nurse called before the surgery, giving me all sorts of dos and don’ts: no eating, drinking, or smoking cigars after 9 p.m. the evening before, take a shower, do not apply facial or hair products, etc.

Which of these rules are really necessary? The nurses tend not to explain why, which invites people to push the boundaries. What happens if I take the last cigar puff at 10:30 pm (which I did)? What’s the magic behind fasting for 12 hours before surgery? Why isn’t it six or twenty-four? No water, seriously? Won’t dehydration undermine recovery? What happens if I resort to rule-breaking?

I woke up at 6:30 am, drank the 4 ounces of water left in a bottle, showered (out of respect for the surgeons and nurses), and otherwise maintained my fast.

After slipping on my hospital gown, the anesthesiologist arrived to let me know how they would put me under. He asked when I last had something to eat or drink. I had finished dinner at 7 pm yesterday and drank 4 ounces of water at 0630.

The time was 8:30, and the doctor said, “Water takes about two hours to run through your system, so we are ok. Some people experience nausea under anesthesia, so we want to make sure your stomach is empty because you can die of suffocation if you vomit.”

Now I get it. The doctor gave me vivid details on why patients should fast and for how long. If I ever have another surgery, I’ll be sure to stop eating 12 hours beforehand and not drink water two hours beforehand.

I could deduce the logic behind most rules, but not all of them. People are more likely to skirt the rules when they don’t get the logic. Respect for the rules signals a healthy business, so you want people to follow your standards voluntarily. Buy–in makes accountability much more manageable.

Here’s how you can improve voluntary compliance with your standards:

- Use the “X so that Y” formula to describe your standards. “Don’t drink water for two hours before your surgery so that you don’t choke on your own vomit from the anesthesia,” for example.

- If you cannot describe a compelling Y for a given rule, you have good reason to discard or modify it. There’s no reason I couldn’t drink some water early that morning, even though the nurse said nothing after 9 pm. The rule seemed ludicrous, and it was. Resist the urge to add excessive safety buffers, or people will stop taking your rules seriously.

- When it comes to adding or modifying standards, enlist the people most affected by them in co-creation. People tend not to design self-defeating rules, so that you will have automatic buy-in for co-created ones.

- Encourage your employees to ask “why” about your standards, which is a good forcing function for you to ensure the Y part of “X so that Y” is compelling.

When I started asking doctors and nurses the why behind their do’s and don’ts, I got better and more customized responses.

The best leaders are humble about their rules. Just because you say a given rule is important does not mean people believe you, especially if you don’t obey the rule yourself.

Make your rules explicit, make them count, and eliminate the ones that have outlived their usefulness.

If you are ready to take your culture to the next level, I have some excellent options.

First, you can join my Building an Inspiring Culture® program in the self-directed or live-led versions. You’ll receive short, crisp videos, clear step-by-step processes, and implementation assignments to apply the lessons at work.

A workshop is a second option. In it, I will walk you through the tools that build an inspiring culture and help you apply them in ways that work for you and your business.

Finally, an off-site retreat can be a powerful experience for you and your team to strengthen trust, streamline communication, and create shared understanding. My clients love doing them outside at battlefields or national parks.

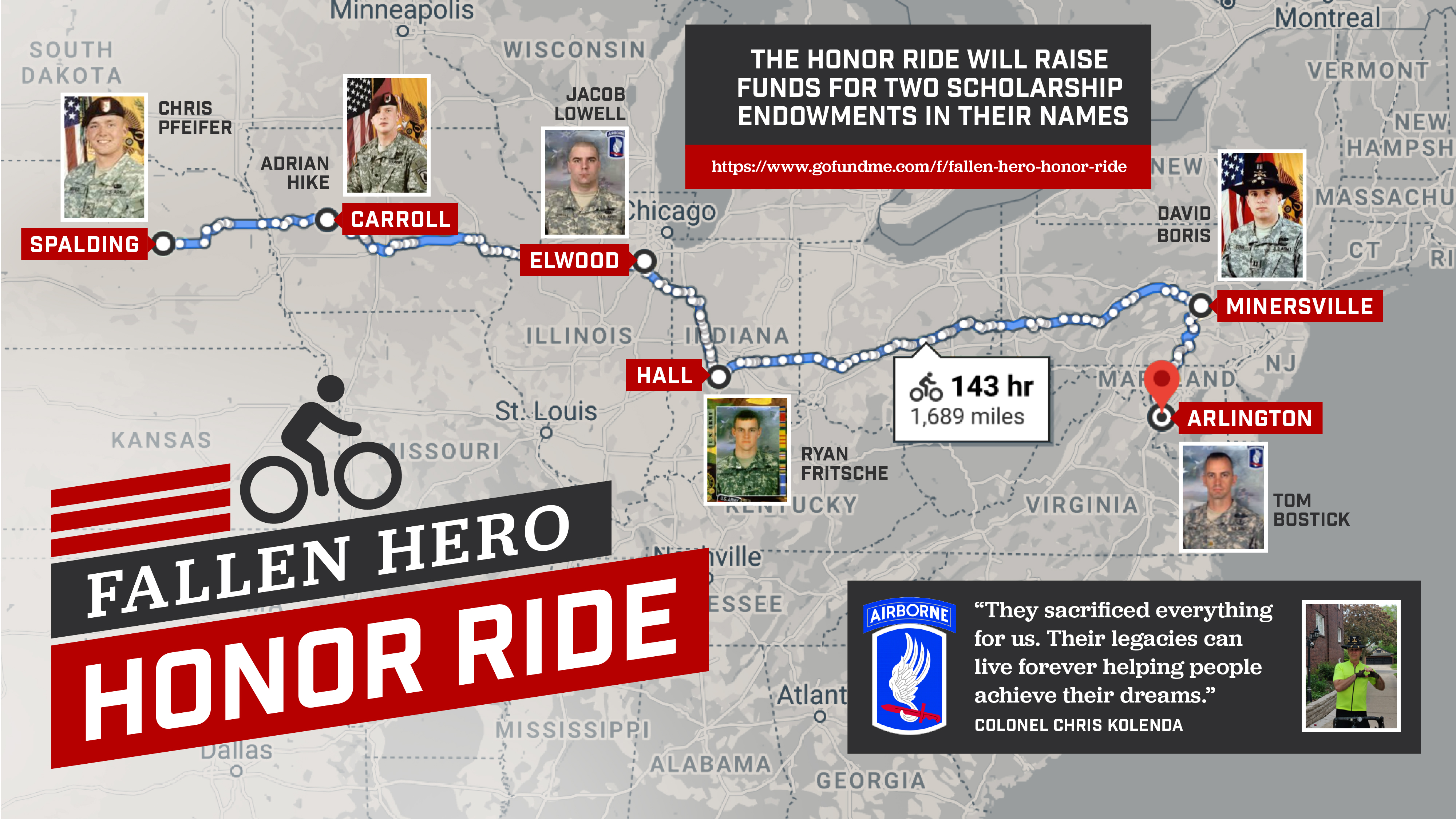

I’ll begin the ride in Spalding, Nebraska, where Chris Pfeifer is buried, and proceed through Carroll, Iowa, to visit Adrian Hike’s final resting place and Elwood, Illinois, to see Jacob Lowell’s grave. The route turns south to Hall, Indiana, to see Ryan Fritsche’s site and Minersville, Pennsylvania, where Dave Boris is buried. The ride concludes at gravesite 8755, section 60, Arlington National Cemetery, where Tom Bostick rests in peace.

I’ll begin the ride in Spalding, Nebraska, where Chris Pfeifer is buried, and proceed through Carroll, Iowa, to visit Adrian Hike’s final resting place and Elwood, Illinois, to see Jacob Lowell’s grave. The route turns south to Hall, Indiana, to see Ryan Fritsche’s site and Minersville, Pennsylvania, where Dave Boris is buried. The ride concludes at gravesite 8755, section 60, Arlington National Cemetery, where Tom Bostick rests in peace.